Essential unmodified excerpts on Management, Strategy, Organization, and Operational Excellence from classical books and articles:

Management- The Practice of Management by Peter Drucker, 1954

- The Effective Executive by Peter Drucker, 1966

- Strategies for Diversification by Igor Ansoff, 1957

- The Product Portfolio by Bruce Henderson, 1970

- Competitive Strategy by Michael Porter, 1980

- Competitive Advantage by Michael Porter, 1985

- The Innovator's Dilemma by Clayton Christensen, 1997

- How Do Committees Invent? by Melvin Conway, 1968

- Manifesto for Agile Software Development, 2001

- Measure What Matters by John Doerr, 2018

- Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk by Trevor Sesnic, 2021

- DORA's software delivery metrics: the four keys by Nathen Harvey, 2025

Management

The Practice of Management

by Peter Drucker, 1954

What is a Business?

The average businessman when asked what a business is, is likely to answer: "An organization to make a profit." And the average economist is likely to give the same answer. But this answer is not only false; it is irrelevant.

If we want to know what a business is we have to start with its purpose. And its purpose must lie outside of the business itself. In fact, it must lie in society since a business enterprise is an organ of society. There is only one valid definition of business purpose: to create a customer.

Because it is its purpose to create a customer, any business enterprise has two - and only these two - basic functions: marketing and innovation. They are the entrepreneurial functions.

Management by Objectives

To emphasize only profit, for instance, misdirects managers to the point where they may endanger the survival of the business. To obtain profit today they tend to undermine the future.

To manage a business is to balance a variety of needs and goals. This requires judgment. The search for the one objective is essentially a search for a magic formula that will make judgment unnecessary. But the attempt to replace judgment by formula is always irrational; all that can be done is to make judgment possible by narrowing its range and the available alternatives, giving it clear focus, a sound foundation in facts and reliable measurements of the effects and validity of actions and decisions. And this, by the very nature of business enterprise, requires multiple objectives.

At first sight it might seem that different businesses would have entirely different key areas - so different as to make impossible any general theory. It is indeed true that different key areas require different emphasis in different businesses - and different emphasis at different stages of the development of each business. But the areas are the same, whatever the business, whatever the economic conditions, whatever the business's size or stage of growth.

There are eight areas in which objectives of performance and results have to be set: Market standing; innovation; productivity; physical and financial resources; profitability; manager performance and development; worker performance and attitude; public responsibility.

The Effective Executive

by Peter Drucker, 1966

What Makes an Effective Executive?

Effectiveness is a discipline. And, like every discipline, effectiveness can be learned and must be earned. Effective executives differ widely in their personalities, strengths, weaknesses, values, and beliefs. All they have in common is that they get the right things done.- They asked, "What needs to be done?"

- They asked, "What is right for the enterprise?"

- They developed action plans.

- They took responsibility for decisions.

- They took responsibility for communicating.

- They were focused on opportunities rather than problems.

- They ran productive meetings.

- They thought and said "we" rather than "I."

Effectiveness Can Be Learned

- Effective executives know where their time goes. They work systematically at managing the little of their time that can be brought under their control.

- Effective executives focus on outward contribution. They gear their efforts to results rather than to work. They start out with the question, "What results are expected of me?" rather than with the work to be done, let alone with its techniques and tools.

- Effective executives build on strengths - their own strengths, the strengths of their superiors, colleagues, and subordinates; and on the strengths in the situation, that is, on what they can do. They do not build on weakness. They do not start out with the things they cannot do.

- Effective executives concentrate on the few major areas where superior performance will produce outstanding results. They force themselves to set priorities and stay with their priority decisions. They know that they have no choice but to do first things first - and second things not at all. The alternative is to get nothing done.

- Effective executives, finally, make effective decisions. They know that this is, above all, a matter of system - of the right steps in the right sequence. They know that an effective decision is always a judgment based on "dissenting opinions" rather than on "consensus on the facts." And they know that to make many decisions fast means to make the wrong decisions. What is needed are few, but fundamental, decisions. What is needed is the right strategy rather than razzle-dazzle tactics.

Know Thy Time

Effective executives, in my observation, do not start with their tasks. They start with their time. And they do not start out with planning. They start by finding out where their time actually goes. Then they attempt to manage their time and to cut back unproductive demands on their time. Finally they consolidate their "discretionary" time into the largest possible continuing units. This three-step process:- Recording time

- Managing time

- Consolidating time is the foundation of executive effectiveness

What Can I Contribute?

The man who focuses on efforts and who stresses his downward authority is a subordinate no matter how exalted his title and rank. But the man who focuses on contribution and who takes responsibility for results, no matter how junior, is in the most literal sense of the phrase, "top management." He holds himself accountable for the performance of the whole.Making Strength Productive

The effective executive makes strength productive. He knows that one cannot build on weakness. To achieve results, one has to use all the available strengths - the strengths of associates, the strengths of the superior, and one's own strengths. These strengths are the true opportunities. To make strength productive is the unique purpose of organization. It cannot, of course, overcome the weaknesses with which each of us is abundantly endowed. But it can make them irrelevant.The task of an executive is not to change human beings. Rather, as the Bible tells us in the parable of the Talents, the task is to multiply performance capacity of the whole by putting to use whatever strength, whatever health, whatever aspiration there is in individuals.

First Things First

If there is any one "secret" of effectiveness, it is concentration. Effective executives do first things first and they do one thing at a time.Courage rather than analysis dictates the truly important rules for identifying priorities:

- Pick the future as against the past;

- Focus on opportunity rather than on problem;

- Choose your own direction - rather than climb on the bandwagon;

- Aim high, aim for something that will make a difference, rather than for something that is "safe" and easy to do.

The Elements of Decision-Making

- The first question the effective decision-maker asks is: "Is this a generic situation or an exception?" "Is this something that underlies a great many occurrences? Or is the occurrence a unique event that needs to be dealt with as such?" The generic always has to be answered through a rule, a principle. The exceptional can only be handled as such and as it comes;

- The definition of the specifications which the answer to the problem had to satisfy, that is, of the "boundary conditions";

- The thinking through what is "right," that is, the solution which will fully satisfy the specifications before attention is given to the compromises, adaptations, and concessions needed to make the decision acceptable;

- The building into the decision of the action to carry it out;

- The "feedback" which tests the validity and effectiveness of the decision against the actual course of events.

Effective Decisions

A decision is a judgment. It is a choice between alternatives. It is rarely a choice between right and wrong. It is at best a choice between "almost right" and "probably wrong" - but much more often a choice between two courses of action neither of which is provably more nearly right than the other.Strategy

Strategies for Diversification

by Igor Ansoff, 1957

If we let P represent the product line and M the corresponding set of missions, then the pair of P and M is a product-market strategy. For our purposes, the concept of a mission is more useful in describing market alternatives than would be the concept of a "customer," since a customer usually has many different missions, each requiring a different product.

| Markets | |||||

| M0 | M1 | M2 | Mm | ||

|

Product Line |

P0 |

Market Penetration |

Market Development |

||

| P1 |

Product Development |

Diversification | |||

| P2 | |||||

| Pn | |||||

Market penetration is an effort to increase company sales without departing from an original product-market strategy. The company seeks to improve business performance either by increasing the volume of sales to its present customers or by finding new customers for present products.

Market development is a strategy in which the company attempts to adapt its present product line (generally with some modification in the product characteristics) to new missions.

A product development strategy, on the other hand, retains the present mission and develops products that have new and different characteristics such as will improve the performance of the mission.

Diversification is the final alternative. It calls for a simultaneous departure from the present product line and the present market structure.

The Product Portfolio

by Bruce Henderson, 1970

The BCG Matrix

| Market Share | |||

| High | Low | ||

| Growth | High |

* Star |

? Question Mark |

| Low |

$ Cash Cow |

X Pet |

|

The balanced portfolio has:

- Stars whose high share and high growth assure the future;

- Cash cows that supply funds for that future growth;

- Question marks to be converted into stars with the added funds.

Pets are not necessary. They are evidence of failure either to obtain a leadership position during the growth phase, or to get out and cut the losses.

Optimum Cash Flow

| Market Share | ||

| Growth |

* + or - (cash flow modest) |

? - (cash flow large) |

|

$ + (cash flow large) |

X + or - (cash flow modest) |

|

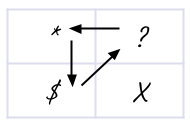

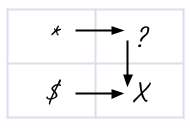

Success Sequence

Disaster Sequence

Competitive Strategy

by Michael Porter, 1980

Every firm competing in an industry has a competitive strategy, whether explicit or implicit.

This strategy may have been developed explicitly through a planning process

or it may have evolved implicitly through the activities of the various functional departments of the firm.

Essentially, developing a competitive strategy is developing a broad formula for how a business is going to

compete,

what its goals should be, and what policies will be needed to carry out those goals.

at the broadest level formulating competitive strategy involves the consideration of

four key factors that determine the limits of what a company can successfully accomplish.

at the broadest level formulating competitive strategy involves the consideration of

four key factors that determine the limits of what a company can successfully accomplish.

The essence of formulating competitive strategy is relating a company to its environment.

Although the relevant environment is very broad, encompassing social as well as economic forces,

the key aspect of the firm's environment is the industry or industries in which it competes.

The essence of formulating competitive strategy is relating a company to its environment.

Although the relevant environment is very broad, encompassing social as well as economic forces,

the key aspect of the firm's environment is the industry or industries in which it competes.

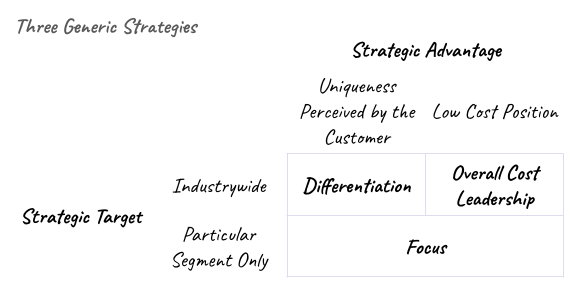

In coping with the five competitive forces, there are three potentially successful generic

strategic approaches to outperforming other firms in an industry:

In coping with the five competitive forces, there are three potentially successful generic

strategic approaches to outperforming other firms in an industry:

- Overall cost leadership

- Differentiation

- Focus

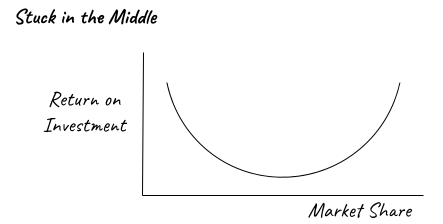

The converse of the previous discussion is that the firm failing to develop

its strategy in at least one of the three directions - a firm that is “stuck in the middle” -

is in an extremely poor strategic situation.

The converse of the previous discussion is that the firm failing to develop

its strategy in at least one of the three directions - a firm that is “stuck in the middle” -

is in an extremely poor strategic situation.

Competitive Advantage

by Michael Porter, 1985

While Competitive Strategy concentrates on the industry, Competitive Advantage concentrates on the firm.

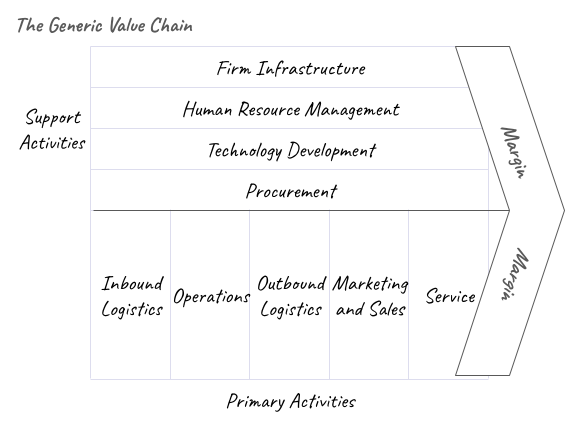

Competitive advantage cannot be understood by looking at a firm as a whole. It stems from the many discrete activities a firm performs in designing, producing, marketing, delivering, and supporting its product.

The value chain displays total value, and consists of value activities and margin. Value activities are the physically and technologically distinct activities a firm performs. These are the building blocks by which a firm creates a product valuable to its buyers. Margin is the difference between total value and the collective cost of performing the value activities.

Value activities are therefore the discrete building blocks of competitive advantage.

How each activity is performed combined with its economics will determine

whether a firm is high or low cost relative to competitors.

How each value activity is performed will also determine its contribution to buyer needs and hence

differentiation.

Comparing the value chains of competitors exposes differences that determine competitive advantage.

Value activities are therefore the discrete building blocks of competitive advantage.

How each activity is performed combined with its economics will determine

whether a firm is high or low cost relative to competitors.

How each value activity is performed will also determine its contribution to buyer needs and hence

differentiation.

Comparing the value chains of competitors exposes differences that determine competitive advantage.

The Innovator's Dilemma

by Clayton Christensen, 1997

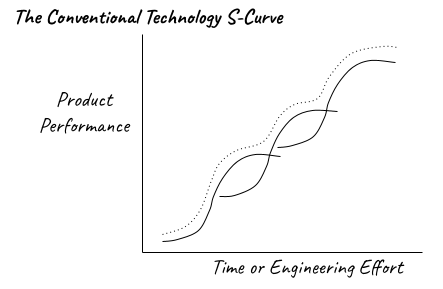

Most new technologies foster improved product performance. I call these sustaining technologies. Some sustaining technologies can be discontinuous or radical in character, while others are of an incremental nature. What all sustaining technologies have in common is that they improve the performance of established products, along the dimensions of performance that mainstream customers in major markets have historically valued. Most technological advances in a given industry are sustaining in character.

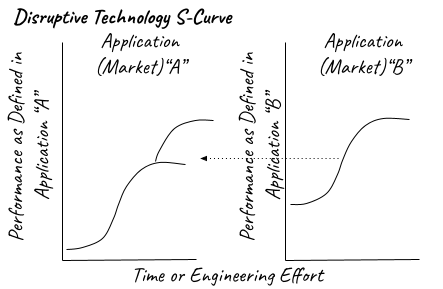

Occasionally, however, disruptive technologies emerge: innovations that result in worse product performance, at least in the near-term. Ironically, in each of the instances studied in this book, it was disruptive technology that precipitated the leading firms' failure.

First, disruptive products are simpler and cheaper; they generally promise lower margins, not greater profits. Second, disruptive technologies typically are first commercialized in emerging or insignificant markets. And third, leading firms' most profitable customers generally don't want, and indeed initially can't use, products based on disruptive technologies. By and large, a disruptive technology is initially embraced by the least profitable customers in a market. Hence, most companies with a practiced discipline of listening to their best customers and identifying new products that promise greater profitability and growth are rarely able to build a case for investing in disruptive technologies until it is too late.

Sound market research and good planning followed by execution according to plan are hallmarks of good management. Because the vast majority of innovations are sustaining in character, most executives have learned to manage innovation in a sustaining context, where analysis and planning were feasible.In dealing with disruptive technologies leading to new markets, however, market researchers and business planners have consistently dismal records. In many instances, leadership in sustaining innovations - about which information is known and for which plans can be made - is not competitively important. In such cases, technology followers do about as well as technology leaders. It is in disruptive innovations, where we know least about the market, that there are such strong first-mover advantages.

This is the innovator's dilemma.

What, then, does account for the success and failure of entrant and established firms? The concept of the value network-the context within which a firm identifies and responds to customers' needs, solves problems, procures input, reacts to competitors, and strives for profit - is central to this synthesis. Within a value network, each firm's competitive strategy, and particularly its past choices of markets, determines its perceptions of the economic value of a new technology. These perceptions, in turn, shape the rewards different firms expect to obtain through pursuit of sustaining and disruptive innovations. In established firms, expected rewards, in their turn, drive the allocation of resources toward sustaining innovations and away from disruptive ones. This pattern of resource allocation accounts for established firms' consistent leadership in the former and their dismal performance in the latter.

the essence of strategic technology management is to identify when the point of inflection on the present technology's S-curve has been passed, and to identify and develop whatever successor technology rising from below will eventually supplant the present approach. The typical framework of intersecting S-curves illustrated in Figure below is a conceptualization of sustaining technological changes within a single value network, where the vertical axis charts a single measure of product performance Because a disruptive technology gets its commercial start in emerging value networks

before invading established networks, an S-curve framework such as that in Figure below

is needed to describe it. Disruptive technologies emerge and progress on their own,

uniquely defined trajectories, in a home value network. If and when they progress to

the point that they can satisfy the level and nature of performance demanded in

another value network, the disruptive technology can then invade it,

knocking out the established technology and its established practitioners, with stunning speed.

Because a disruptive technology gets its commercial start in emerging value networks

before invading established networks, an S-curve framework such as that in Figure below

is needed to describe it. Disruptive technologies emerge and progress on their own,

uniquely defined trajectories, in a home value network. If and when they progress to

the point that they can satisfy the level and nature of performance demanded in

another value network, the disruptive technology can then invade it,

knocking out the established technology and its established practitioners, with stunning speed.

A crucial strategic decision in the management of innovation is whether it is

important to be a leader or acceptable to be a follower. Volumes have been written

on first-mover advantages, and an offsetting amount on the wisdom of waiting until

the innovation's major risks have been resolved by the pioneering firms.

"You can always tell who the pioneers were," an old management adage goes.

"They're the ones with the arrows in their backs."

A crucial strategic decision in the management of innovation is whether it is

important to be a leader or acceptable to be a follower. Volumes have been written

on first-mover advantages, and an offsetting amount on the wisdom of waiting until

the innovation's major risks have been resolved by the pioneering firms.

"You can always tell who the pioneers were," an old management adage goes.

"They're the ones with the arrows in their backs."

Three classes of factors affect what an organization can and cannot do: its resources, its processes, and its values.

Resources include people, equipment, technology, product designs, brands, information, cash, and relationships with suppliers, distributors, and customers. Resources are usually things, or assets—they can be hired and fired, bought and sold, depreciated or enhanced. They often can be transferred across the boundaries of organizations much more readily than can processes and values.

Processes include not just manufacturing processes, but those by which product development, procurement, market research, budgeting, planning, employee development and compensation, and resource allocation are accomplished. One of the dilemmas of management is that, by their very nature, processes are established so that employees perform recurrent tasks in a consistent way, time after time. To ensure consistency, they are meant not to change - or if they must change, to change through tightly controlled procedures. This means that the very mechanisms through which organizations create value are intrinsically inimical to change. Some of the most crucial processes to examine as capabilities or disabilities aren't the obvious value-adding processes involved in logistics, development, manufacturing, and customer service. Rather, they are the enabling or background processes that support investment decision-making. These typically inflexible processes are where many organizations' most serious disabilities in coping with change reside.

An organization's values are the standards by which employees make prioritization decisions. A key metric of good management, in fact, is whether such clear and consistent values have permeated the organization. Clear, consistent, and broadly understood values, however, also define what an organization cannot do. One of the bittersweet rewards of success is, in fact, that as companies become large, they literally lose the capability to enter small emerging markets. This disability is not because of a change in the resources within the companies—their resources typically are vast. Rather, it is because their values change.

Despite beliefs spawned by popular change-management and reengineering programs, processes are not nearly as flexible or "trainable" as are resources - and values are even less so. The processes that make an organization good at outsourcing components cannot simultaneously make it good at developing and manufacturing components in-house. Values that focus an organization's priorities on high-margin products cannot simultaneously focus priorities on low-margin products. This is why focused organizations perform so much better than unfocused ones: their processes and values are matched carefully with the set of tasks that need to be done.

For these reasons, managers who determine that an organization's capabilities aren't suited for a new task, are faced with three options through which to create new capabilities. They can:

- Acquire a different organization whose processes and values are a close match with the new task

- Try to change the processes and values of the current organization

- Separate out an independent organization and develop within it the new processes and values that are required to solve the new problem

Organization

How Do Committees Invent?

by Melvin Conway, 1968

A contract research organization had eight people who were to produce a COBOL and an ALGOL compiler. After some initial estimates of difficulty and time, five people were assigned to the COBOL job and three to the ALGOL job. The resulting COBOL compiler ran in five phases, the ALGOL compiler ran in three.

Two military services were directed by their Commander-in-Chief to develop a common weapon system to meet their respective needs. After great effort they produced a copy of their organization chart.

Consider the operating computer system in use solving a problem. At a high level of examination, it consists of three parts: the hardware, the system software, and the application program. Corresponding to these subsystems are their respective designers: the computer manufacturer's engineers, his system programmers, and the user's application programmers. (Those rare instances where the system hardware and software tend to cooperate rather than merely tolerate each other are associated with manufacturers whose programmers and engineers bear a similar relationship.)

Any organization that designs a system will inevitably produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.

Operational Excellence

Manifesto for Agile Software Development

2001

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value:- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

Principles behind the Agile Manifesto

Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software. Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer's competitive advantage. Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale. Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project. Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done. The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation. Working software is the primary measure of progress. Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely. Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility. Simplicity--the art of maximizing the amount of work not done--is essential. The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams. At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.Measure What Matters

by John Doerr, 2018

Ideas are easy. Execution is everything.Google's OKR Playbook

Writing good OKRs isn't easy, but it's not impossible, either. Pay attention to the following simple rules: Objectives are the "Whats." They:- express goals and intents;

- are aggressive yet realistic;

- must be tangible, objective, and unambiguous; should be obvious to a rational observer whether an objective has been achieved.

- The successful achievement of an objective must provide clear value for Google.

- express measurable milestones which, if achieved, will advance objective(s) in a useful manner to their constituents;

- must describe outcomes, not activities. If your KRs include words like "consult," "help," "analyze," or "participate," they describe activities. Instead, describe the end-user impact of these activities: "publish average and tail latency measurements from six Colossus cells by March 7," rather than "assess Colossus latency";

- must include evidence of completion. This evidence must be available, credible, and easily discoverable. Examples of evidence include change lists, links to docs, notes, and published metrics reports.

Dr. Grove's Basic OKR Hygiene

- Less is more. "A few extremely well-chosen objectives," Grove wrote, "impart a clear message about what we say 'yes' to and what we say 'no' to." A limit of three to five OKRs per cycle leads companies, teams, and individuals to choose what matters most. In general, each objective should be tied to five or fewer key results."

- Set goals from the bottom up. To promote engagement, teams and individuals should be encouraged to create roughly half of their own OKRs, in consultation with managers. When all goals are set top-down, motivation is corroded.

- No dictating. OKRs are a cooperative social contract to establish priorities and define how progress will be measured. Even after company objectives are closed to debate, their key results continue to be negotiated. Collective agreement is essential to maximum goal achievement.

- Stay flexible. If the climate has changed and an objective no longer seems practical or relevant as written, key results can be modified or even discarded mid-cycle.

- Dare to fail. "Output will tend to be greater," Grove wrote, "when everybody strives for a level of achievement beyond [their] immediate grasp. . . . Such goal-setting is extremely important if what you want is peak performance from yourself and your subordinates." While certain operational objectives must be met in full, aspirational OKRs should be uncomfortable and possibly unattainable. "Stretched goals," as Grove called them, push organizations to new heights.

- A tool, not a weapon. The OKR system, Grove wrote, "is meant to pace a person—to put a stopwatch in his own hand so he can gauge his own performance. It is not a legal document upon which to base a performance review." To encourage risk taking and prevent sandbagging, OKRs and bonuses are best kept separate.

- Be patient; be resolute. Every process requires trial and error. As Grove told his iOPEC students, Intel "stumbled a lot of times" after adopting OKRs: "We didn't fully understand the principal purpose of it. And we are kind of doing better with it as time goes on." An organization may need up to four or five quarterly cycles to fully embrace the system, and even more than that to build mature goal muscle.

MBOs vs. OKRs

| MBOs | Intel OKRs |

|---|---|

| "What" | "What" and "How" |

| Annual | Quarterly or Monthly |

| Private and Siloed | Public and Transparent |

| Top-down | Bottom-up or Sideways (~50%) |

| Tied to Compensation | Mostly Divorced from Compensation |

| Risk Averse | Aggressive and Aspirational |

Culture

In Project Aristotle, an internal Google study of 180 teams, standout performance correlated to affirmative responses to these five questions:- Structure and clarity: Are goals, roles, and execution plans on our team clear?

- Psychological safety: Can we take risks on this team without feeling insecure or embarrassed?

- Meaning of work: Are we working on something that is personally important for each of us?

- Dependability: Can we count on each other to do high-quality work on time?

- Impact of work: Do we fundamentally believe that the work we're doing matters?

Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk

by Trevor Sesnic, 2021

Musk overviewed his five step engineering process, which must be completed in order:- Make the requirements less dumb. The requirements are definitely dumb; it does not matter who gave them to you. He notes that it's particularly dangerous if an intelligent person gives you the requirements, as you may not question the requirements enough. "Everyone's wrong. No matter who you are, everyone is wrong some of the time." He further notes that “all designs are wrong, it's just a matter of how wrong.”

- Try very hard to delete the part or process. If parts are not being added back into the design at least 10% of the time, not enough parts are being deleted. Musk noted that the bias tends to be very strongly toward "let's add this part or process step in case we need it.” Additionally, each required part and process must come from a name, not a department, as a department cannot be asked why a requirement exists, but a person can.

- Simplify and optimize the design. This is step three as the most common error of a smart engineer is to optimize something that should not exist.

- Accelerate cycle time. Musk states "you're moving too slowly, go faster! But don't go faster until you've worked on the other three things first."

- Automate. An important part of this is to remove in-process testing after the problems have been diagnosed; if a product is reaching the end of a production line with a high acceptance rate, there is no need for in-process testing.

DORA's software delivery metrics: the four keys

by Nathen Harvey, 2025

The four key metrics function as:- Leading indicators for organizational performance and employee well-being

- Lagging indicators for software development and delivery practices.

Throughput and stability

DORA's four keys can be divided into metrics that show the throughput of software changes, and metrics that show stability of software changes. This includes changes of any kind, including changes to configuration and changes to code.Throughput

Throughput measures the velocity of changes that are being made. DORA assesses throughput using the following metrics:- Change lead time - This metric measures the time it takes for a code commit or change to be successfully deployed to production. It reflects the efficiency of your software delivery process.

- Deployment frequency - This metric measures how often application changes are deployed to production. Higher deployment frequency indicates a more efficient and responsive delivery process.

Stability

Stability measures the quality of the changes delivered and the team's ability to repair failures. DORA assesses stability using the following metrics:- Change fail percentage - This metric measures the percentage of deployments that cause failures in production, requiring hotfixes or rollbacks. A lower change failure rate indicates a more reliable delivery process.

- Failed deployment recovery time - This metric measures the time it takes to recover from a failed deployment. A lower recovery time indicates a more resilient and responsive system.